I’ve picked up a lot of DRM-free comic books from sites like Humble Bundle and Fanatical lately.

I found myself wanting to have a way to read comic books on my tablet that didn’t involve manually copying each of the massive comic files from my computer onto my old tablet (with very limited storage space) via USB each time.

As I’ve also recently set up Jellyfin for locally hosting video files (backing up my DVD collection and making them easier to watch), I started having a look into services for hosting book files locally too.

Here’s what I found, and what annoying hoops I had to jump through.

Part 0: The Goal

The ideal setup for me is to have a service running on my cheap mini Linux PC that I can read or download my digital comic books from. I only care about having this service running on my local network, as it’s only for personal use, and I can download books if I want to read them outside of the house. I want a service that will make it easy for me to understand what order I’m meant to read them (because comics can be nasty like that) and also keep track of what I’ve read so that I can make my way through a series.

I figured this out for video streaming via Jellyfin, so surely books are even easier, right? Right?

Why can’t I just use Jellyfin?

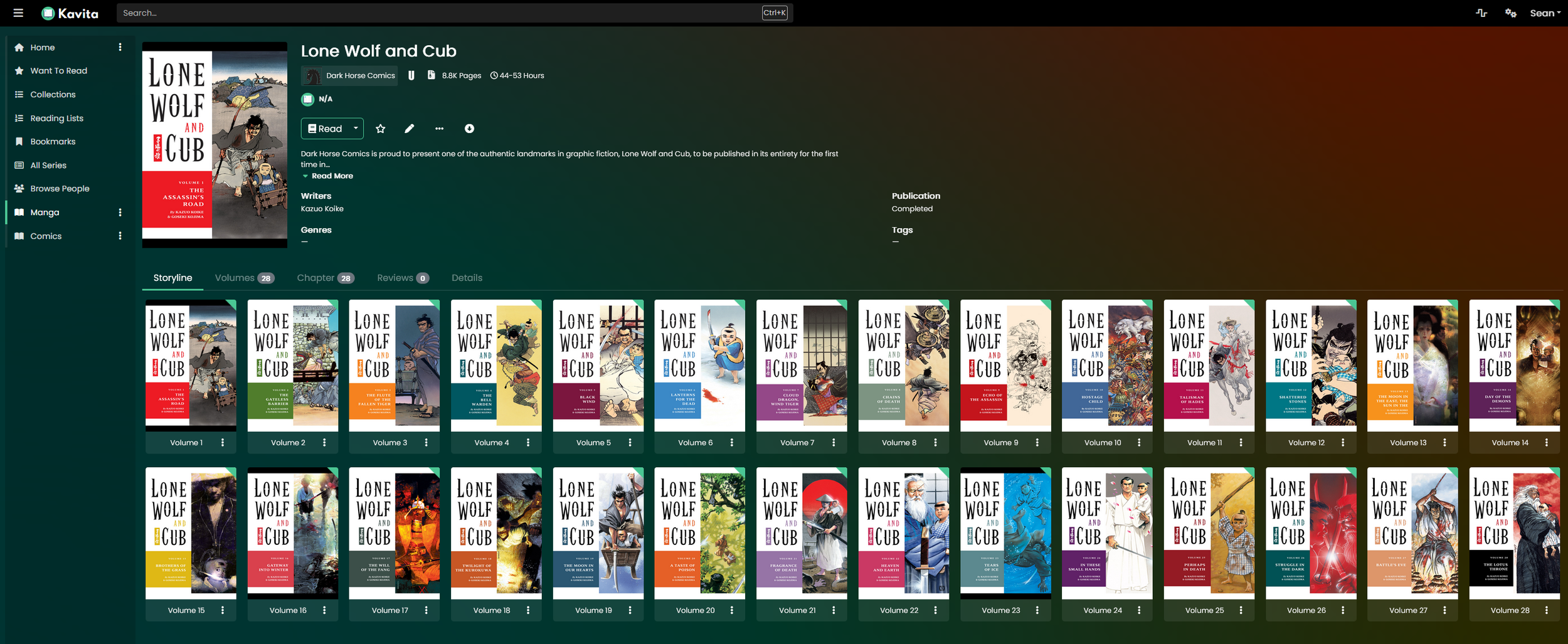

Jellyfin does actually support books and comics with an optional plugin! Jellyfin even seemed to lay out my comics in exactly the way I want - using my exact folder structure!

But there was a big catch. The reader is mostly useless, especially with the Jellyfin Android app, which is what I would want to use to read books on my tablet. And it doesn’t support all the metadata that Kavita does. It’s somewhat usable - but not good.

Jellyfin’s books displayed in my own folder structure, with previews… if only the reader was any good!

So while looking up how best to set up Jellyfin, I found Kavita and decided I’d try and use that instead.

Part 1: Getting the books

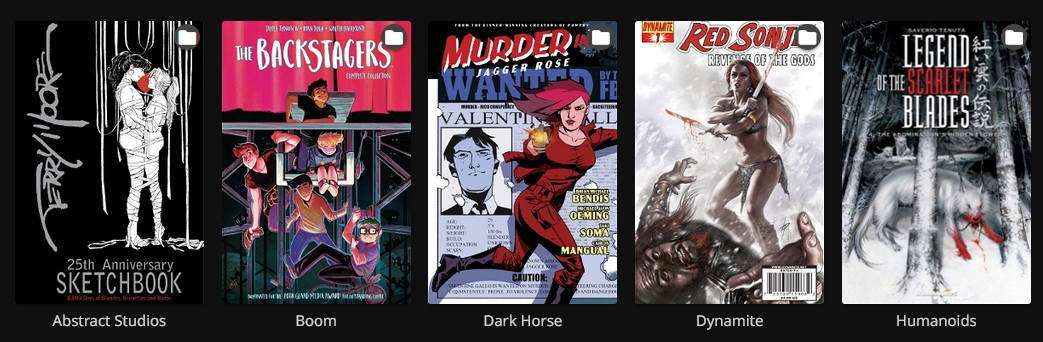

I buy DRM-free books from various sources like Humble Bundle and Fanatical, and I’ve noticed that some websites like Rebellion (Judge Dredd) sell DRM free copies of their comics too!

DRM Free is an absolute necessity for the process I’m doing, because I’m converting files and attaching new data to them.

1.1 What format to download?

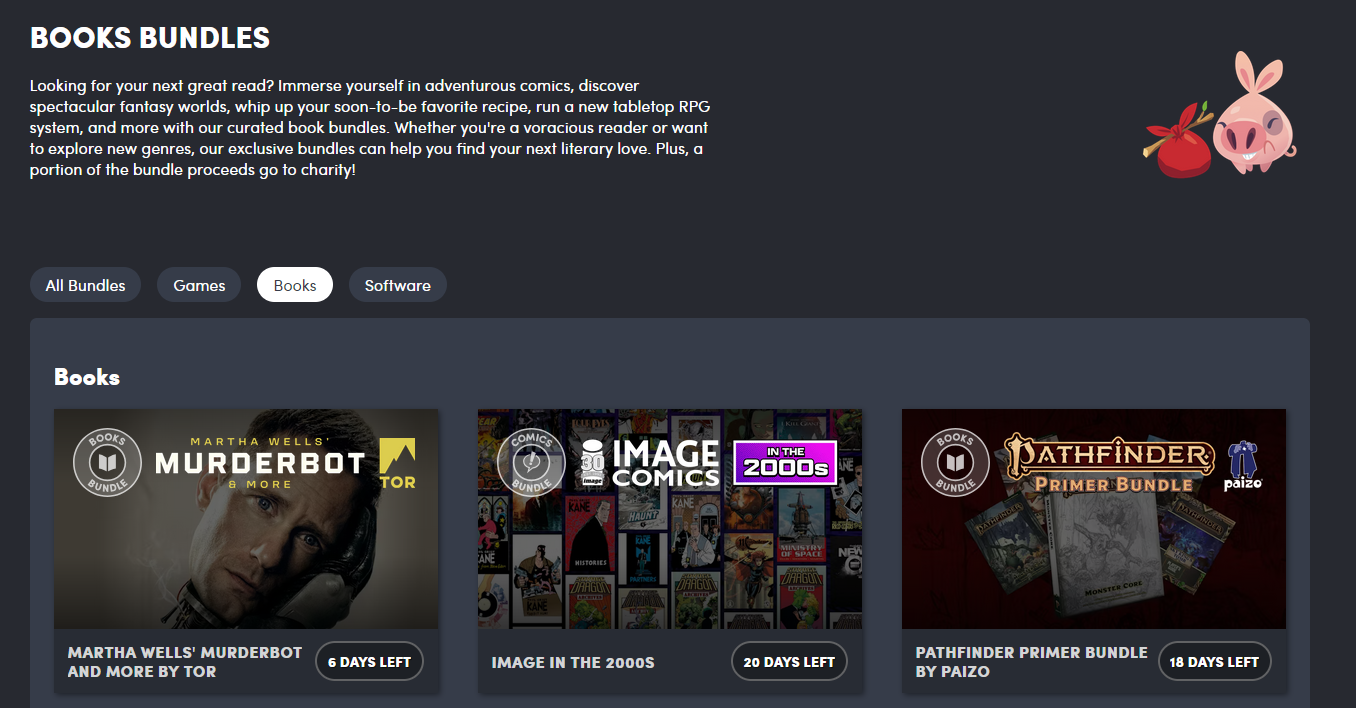

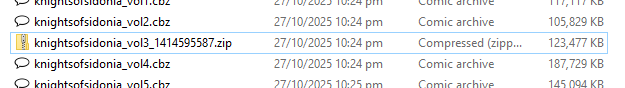

Note the suspiciously small 17.2MB CBZ file in the second row

If offered, it’s generally best to download them directly in .cbz format. However, in some cases that I’ve seen, occasionally the .cbz files are very low quality and I have better luck downloading the .pdf version of the comic at a much large filesize and then converting it to .cbz myself. Now when I get a bundle I often do a test download of each format for a comic and see if they look significantly different. If the .cbz is all good I’ll grab them, if they’re worse then I’ll convert the .pdf or .epub offerings!

1.2 Bulk Downloading

I always double check my files when doing bulk downloading from Humble or Fanatical… In my experience, Firefox will often skip random books and I have to double check every book offered to every book downloaded. I find that Chrome does a better job of making sure all of the files actually get downloaded.

1.3 Keep an eye out for wrong books

A couple of times the .cbz file has been for a totally wrong book too, so that’s something to watch out for. I got ‘Paper Girls’ series in a Humble Bundle, and the .cbz and .pdf formats of book 4 (of 6) was the totally wrong book. Thankfully the .epub was the correct one and I could convert it myself!

1.4 .zip format comic?

Occasionally for some reason Humble will offer a comic file that comes down as a .zip.

In this case, just rename it to .cbz. CBZ is just a zip folder of images. I don’t know why it’s named wrong, but every time I’ve seen this, it works totally fine to just rename it from .zip to .cbz.

Part 2: Comic File Types

The first thing you’ll run into is that you’re going to end up with an assortment of different file types, especially if you’re getting book bundles from different publishers or sources. I’ll break them down into comic-specific pros and cons.

2.1: .pdf files

You’re probably familiar with these. They tend to have massive file sizes and are often quite high quality. They have some perks - sometimes they aren’t purely images, they’re basically the source files for the books themselves (I assume), so often the dialogue text is added with fonts rather than being baked into the images, so you can select text, and due to the way fonts are rendered, the text itself can be higher resolution than the surrounding art.

You can also search for text (as long as it was written with a font and not part of the image itself).

I haven’t really found a good use for this functionality, really. Plus, the files are very resource-intensive.I find them quite slow to load and scroll through, even on a very powerful home computer.

Selectable, scaling text in a .PDF

One big downside of .pdf files is that you can’t easily embed comic metadata in them, any bonus metadata sits in a file alongside the .pdf, which makes editing metadata for them a lot more annoying - I’ll get into this later.

2.2: .epub files

This is the classic open source eBook format. It was created as an alternative to .mobi, which is Amazon’s proprietary format for Kindle books. I read some interesting history on the source of .mobi and .epub here. An .epub file is basically a zip file containing HTML and CSS, as well as (at least, for comics) a folder of images. You can even extract it with 7zip as if it were a .zip file. And due to this (which will come into play later), you can run python zip commands on them.

The metadata is stored in .opf files within the zip.

These are fantastic for regular, non-comic books!

2.3: .cbz files

This is an open source format created specifically for comic files. I really like this format, because it’s super simple - even more simple than .epub. It’s a zip with a bunch of images in it, named in the order that you see them.

Because they are so simple, there are plenty of great free comic reading apps available for .cbz files.

The metadata is a file called ‘ComicInfo.xml’ in the zip, next to the images.

Part 3: Converting Files

I’ve come to the conclusion that for hosting comics, it’s much easier to just make all of my comics .cbz. I’ll get into the reasons by the end of this, but I wish I’d just done the conversion up front. I’ve had to redo a lot of work because I left half my collection in .pdf or .epub formats.

3.1 PDF to CBZ

.pdf files are really annoying for tagging with metadata -they would have to have the metadata as a separate file, and I can’t be bothered figuring that out or managing it, it’s a lot more work.

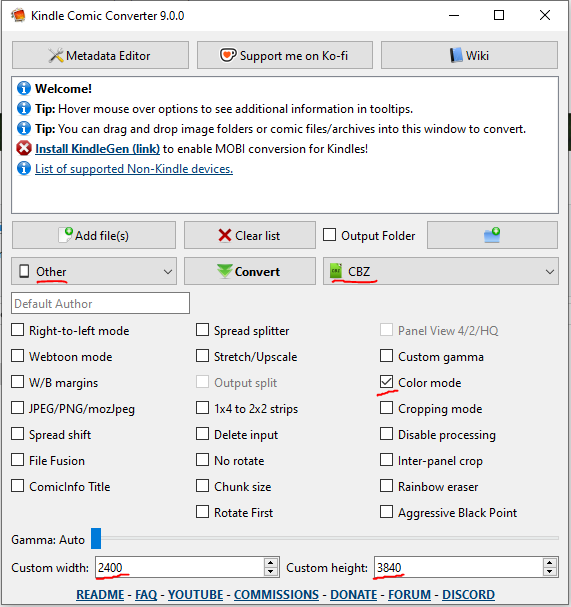

For converting .pdf to .cbz, I use ‘Kindle Comic Converter 9.0.0’. The tool was made to get comic .pdf files to the appropriate size and format for use on various eReader devices, so it has lots of great preset settings for this purpose - if you just want to read manga on an eReader or something, you don’t have to go much further than this. However, I want colour comics on high-resolution devices, so I have to tweak the settings.

These are the settings I use 99% of the time.

I set the output device to ‘other’ so that I can set the custom resolution.

I tick 'Color mode’ so that the output doesn’t get set to monochrome. I have a colour Kobo eReader anyway, so I’d toggle this even if I was intending to read the files on my Kobo.

I set the Custom width/height values to 2400 x 3840, which is the max that the app will let me enter. I don’t know why the app is capped to these values - maybe it’s just the highest resolution of the devices it’s expecting. I want high-resolution .cbz files so I use the max settings. Sometimes this resolution is actually lower than the .pdf’s resolution, so there is a reduction of quality - but 2400 x 3840 is a good resolution even when zoomed in on a panel, so I don’t mind this concession.

I set the output dropdown to CBZ.

Once I’ve changed my settings, I hit Convert and always check the output!

3.1b: Landscape .pdfs:

Note that for one .pdf file that I had that was in a very wide landscape format (like a newspaper cartoon), I had to change the width and height so that the ratio matched the ratio of the source .pdf - otherwise it split each page into two to make them profile! By changing the output resolution to landscape, it stopped the application from splitting the pages into two images.

3.1c: Reverse .pdfs:

One .pdf file that I got from a bundle was in totally reverse order, a Witcher manga comic. I had to convert it to .cbz with KCC, then unzipped the .cbz into a folder, then renamed the image files inside into reverse order, then zipped it back up and renamed it to .cbz again.

Because .cbz is just a zip of image files, you can just do this!

3.1d: Weirdly Small Images

One book in a Humble bundle offered a .cbz file that was completely unreadable, as some of the images were far too small to read. The .pdf format Humble offered for the same book had a bigger filesize so I grabbed that too, at at least that one was readable when zoomed in. However it still had some weird scaling going on on the images so the pages had different sized images that needed to be zoomed in on. I guess that they had used images of a decent size but they had scaled the pages down or something?

Thankfully, KCC has an option to help fix this - the ‘Stretch/Upscale’ option. Tick this and it will scale the images up to the 2400x3840 but keep the correct aspect ratio. Make sure the box is ticked and not filled in with a square! You may have to click it twice.

With that option ticked, my .cbz file was totally readable. Phew!

3.2: ePub to CBZ

ePubs are a pretty nice format - I didn’t want to have to convert them, but I ran into metadata problems. I’ll get into this more later, but the application that I was using to retrieve comic information, ComicTagger, did not correctly support .epub files due to the difference in metadata structure. It ended up just shoving a new ‘ComicInfo.xml’ file into the .epub, but no other application expects a ‘ComicInfo.xml’ in an .epub so it doesn’t get used anyway, and actually ended up lightly corrupting a few of my .epub files. I could tag them manually through another application like Calibre - but I don’t want to do that. I much prefer a flow that lets me tag in bulk using the same application to try and keep my tags consistent. So, conversion it is.

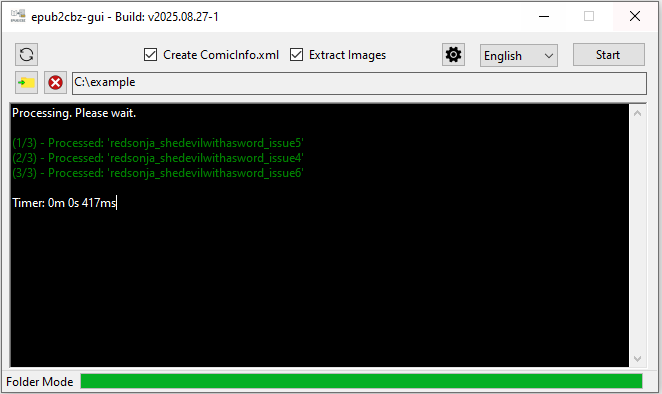

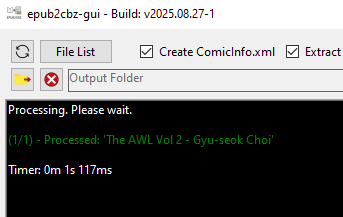

To convert ePub to CBZ, I used epub2cbz-gui. Honestly, I’m not really a fan of this not being open source software - it feels pretty dodgy to just run a .exe file for such a niche purpose without it being open-source - but I gave it a quick scan with Windows Defender and used it anyway. It felt like picking a dropped chip off the floor and giving it a quick blow before eating it.

The software works nicely, though - you can point it to a folder and it’ll run on every .epub in the folder, creating a .cbz for each.

Technically, you could convert .epub to .cbz manually just by extracting the .epub, grabbing the folder of images inside, and then zipping them up and calling it .cbz. I think I read that for some applications, literally just renaming the Comic.epub to Comic.cbz also works, but I think there are flaws in that approach. This epub2cbz-gui application at least tries to bring across some of the .epub’s formatting data, and features like Chapters are carried across to the new .cbz, so it’s a far nicer approach.

One thing to note is that epub2cbz-gui will also migrate any of the .epub’s original metadata across, so if the publisher of your .epub comic have set values on there, they will carry across. This can sometimes get in the way.

3.2b: Did you shove a ComicInfo.xml into your epubs?

One thing I ran into, that hopefully you won’t - because I had already run ComicTagger on all my .epub files and shoved useless ComicInfo.xml files into them, the epub2cbz-gui refused to operate on my .epub files. I had to create a python script to run over all of my .epubs, copy the contents into a temp zip EXCEPT for ComicInfo.xml, then replace the original .epub. Then I could run them through epub2cbz-gui. This probably won’t apply to anyone else, but it was yet another bloody annoying roadblock for me.

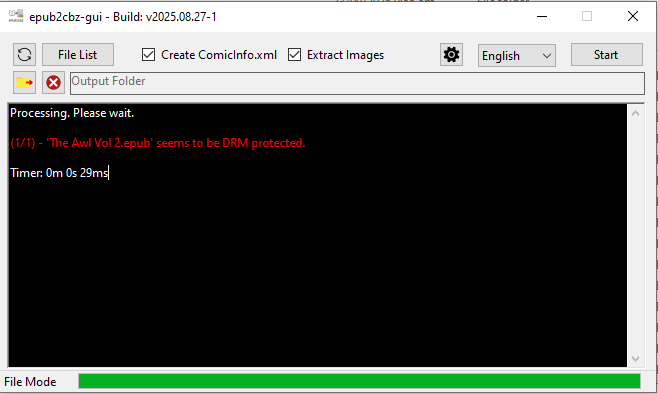

3.3c: Are your .epubs DRM-protected?

I haven’t run into this very often, but I got some comic .epubs from a Fanatical bundle that had some DRM protection that prevented me from running them through epub2cbz-gui. The conversion application shows the message “[book] seems to be DRM protected”.

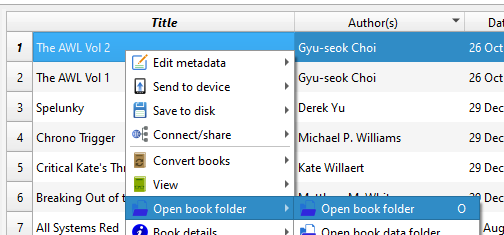

Thankfully I managed to find a pretty simple workaround using Calibre (which I use to copy books onto my Kobo e-reader device). Calibre makes its own copy of the file in its own internal folder structure, and renames it in its own way. This can be really annoying, and it’s why I don’t use it for my comic organisation. However, it does have the ability to strip DRM from an .epub file!

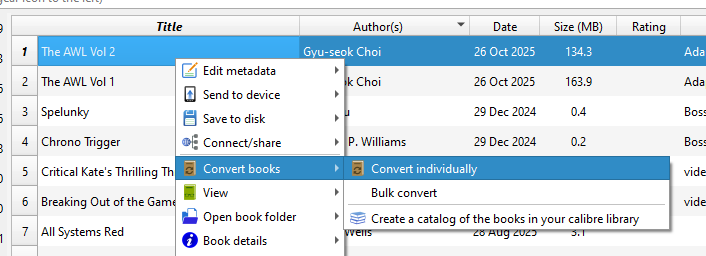

The first step is to open the file in Calibre, then right click on it and select Convert books -> Convert individually

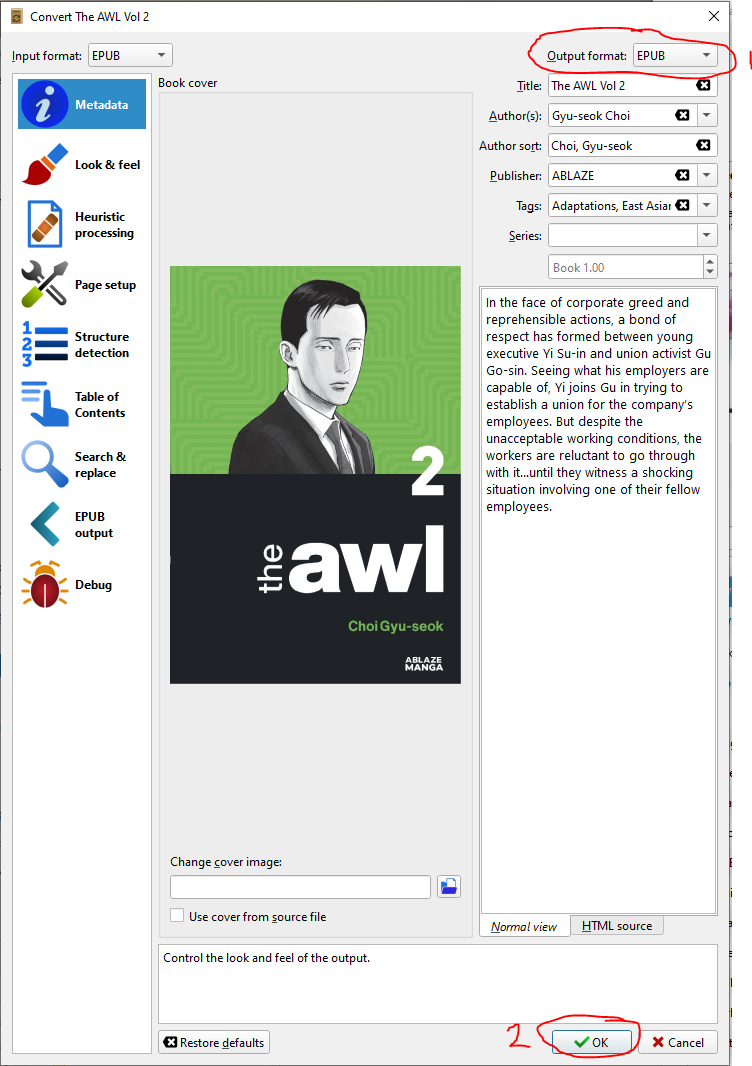

Then, change the Output format setting to EPUB (converting .epub to .epub!) and then click OK.

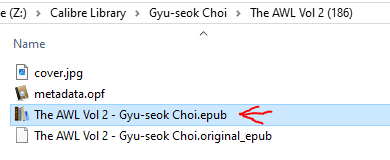

This will process for a little while, it should show a notification. When it’s done, find the folder that Calibre has put your new file. Right click on the file and click Open book folder -> Open book folder.

Now, grab the new file - it will likely have a new filename including the author/writer of the book. The original is still there, and you’ll still have your original original file, if you haven’t deleted it, from before you opened it into Calibre.

Now, drag this new file into epub2cbz-gui (make sure it’s in ‘file’ mode and not ‘folder’ mode).

Success!! Now I have a .cbz file from my DRM-protected .epub file, so I can edit its metadata using ComicTagger.

Part 4: Comic Terminology

If you’re familiar with comics, feel free to skip this part - but understanding it helps with naming your files and grabbing metadata.

4.1 Comics vs. Manga

It seems an odd distinction to make, because they’re all comics, but there are different approaches to the release cadence of western style comics like DC and Marvel vs. Japanese style comics.

Many Western comic series are very long running series that have different writers and artists over their lifetime. This means that you’ll end up with different ‘runs’ by different authors. In long-running series, the ‘numbering’ of the issues will reset multiple times. Most Manga, on the other hand, are written by a single team from start to finish, with very linear and consistent ordering. This makes management of Western style comics much harder to organise!

Due to this, some applications or services will have different settings based on whether a file is labelled as ‘comic’ or ‘manga’. There are metadata-gathering apps that are designed to work specifically on manga, for example.

4.2 Standalone Books

If a book isn’t part of a series at all, it’s a ‘Graphic Novel’ or ‘GN’. Or just a ‘book’, whatever. Easy!

4.3 Issues vs. Volumes vs. Omnibus

The way comics, especially Western comics, are structured is not obvious if you are getting into comics through digital bundles, so I’ll break it down.

Normally, your files will either be a single Issue, a single Volume, or an Omnibus.

4.3b Issues

‘Issues’ are short, often around 22 pages or so. generally the original physically release of a comic is a monthly issue. They’re generally a chapter of a story. In Manga terminology they are just called 'chapters’.

An Issue that doesn’t directly connect to any other issues is often called a ‘one-shot’. One type of one-shot is an ‘Annual’, generally a longer issue that a publisher will put out no more than once a year. To make it even more horrendous, occasionally you’ll get a special case like an ‘issue #100’ that is counting from the very first issue and not the numbering of the previous issue. Then it’ll go back to whatever it was for the next one.

Issues are numbered. It is possible to have multiple duplicate numbers within one IP. For example, there are probably 30 or so ‘Batman #1’ issues because of how many times Batman has had a new run. This gets difficult to deal with when it comes to sorting all your comics out, as you might imagine. Often the year in brackets, i.e. “Batman (2009) #1” is used to differentiate these different issue #1s.

4.3c Volumes

‘Volumes’ are a collection of issues. In physical media Comics parlance, a soft-cover collection of a number of issues is called a ‘Trade Paperback’ or ‘TPB’. TPBs commonly contain 3-5 issues, but it varies. A hardcover collection that is normally physically larger than the paperback and often contains 8-12 issues is called an ‘Oversized Hardcover’ or ‘OSHC’.

Volumes are also numbered, but the number only relates to the number of the volume in relation to the other volumes. A single run of comics might be collected in 8 TPBs and 4 OSHCs, each set with their own numbering.

On top of that, sometimes the volumes have their own name. The example to the left, the hardcover Hellboy ‘Library Edition’ Volume 3 is “Hellboy Volume 3 Conqueror Worm and Strange Places”. Not to be confused with the TPB “Hellboy Volume 3 The Chained Coffin and Others”.

You might think oh, that could be difficult to deal with if your comic files are a mix and match of issues and different sized volumes. And you’d be right!

4.3d Omnibus

‘Omnibus’ is the term for a collection of comic volumes in one book. Normally between 20-40 issues. They make giant files, sometimes over 1gb. They also make enormous, unwieldy books that don’t fit on your shelves or laps.

They could also be called something like ‘Complete Edition’.

4.4 Series

‘Series’ seems obvious, if it’s a Batman comic, the series is Batman, right? …Actually, in many cases it refers to a ‘run’ of comics. For example, Batman has been written by dozens of writers over the years. When Scott Snyder wrote Batman comics in 2011, even though there had been hundreds of Batman issues up till this point, the Issue number changed back to #1 (actually #0 in this case) and he started a new ‘Run’, “Batman 2011 #0”. This is referred to as ‘Snyder’s Batman Run’. Thus, the ‘Series’ in this case is ‘Batman (2011)’, not ‘Batman’. Within a series, there may be one or multiple ‘story arcs’. When Tom King took over writing Batman in 2016, a new series started, ‘Batman (2016)’.

When it comes to metadata tagging, it gets even more annoying. The way volumes are tagged in ComicVine (where a lot of comic metadata apps get their information from), they will use the name of the volume rather than the name of the series in the Series name, like “Hellboy: The Chained Coffin and Others” instead of “Hellboy”. More on that later.

Part 5: Filenames

One thing you’ll notice when you get a bunch of comics from a Humble Bundle is that most of the filenames are something like “thedropsofgod6.epub”. Easy enough for a human to parse, although personally not ideal.

Sometimes you’ll get ones like “hellboyvolume3_thechainedcoffinandothers2ndedition.pdf”. This is a bit rougher to parse even for a human, but for an application that parses comic files to add metadata, it’s awful. The biggest problem is that it has two digits in the filename, ‘volume3” and “2ndedition”. When an application tries to make heads or tails of this, it may trip up on which volume this is.

So, as painful as it is, I highly recommend manually renaming your book files immediately.

Even more painfully, different software and services will have different ideas about how you should name these files.

Here’s what I’ve landed on.

5.1 Naming Single Issues

If your comics are primarily individual issues (the floppy comic standard, normally around 22 pages or so), for example the Adventure Time comics I got from a Humble Bundle, it seems like the standard is to use a # symbol to denote the Issue number. For example:

‘Adventure Time (2012) #001.cbz’

If you don’t know the year, you can retroactively add it later once you’ve pulled down metadata that can hopefully tell you what the year/series is for each of your files. This should be the year correlating to the issue #1 of the ‘run’ for the group of issues you have, for example

‘Adventure Time (2012) #072.cbz’

Even though Adventure Time issue #72 came out in 2018.

Generally text in (brackets) will be ignored by metadata tools, but they help to keep your filenames unique.

5.2 Naming Volumes

5.2b - Volume number

If your comics are volumes rather than issues, you may want to use ‘vol’ before the volume number. One thing I ran into is that if I had a space between vol and the volume number, ComicTagger would include “vol” as part of the series name.

For example, ‘Vinland Saga Vol 5’ gets interpreted by ComicTagger as issue #5 of the series “Vinland Saga Vol”.

Argh! It’s possible to override this name when pulling down metadata - but it seemed easier to me to just name the files without a space. In this case, being a straight forward manga series that doesn’t reset its numbering, I also decided to skip the year in the filename in this case. So, I landed on:

‘Vinland Saga Vol5.cbz’

5.2c - Volumes with subtitles

Some volumes have individual subtitles, not just a number. For example, ‘Black Hammer Volume 3: Age of Doom’. Unfortunately, this is where it gets painful. Often ComicTagger does require the subtitle to find the book’s data, but it also ignores anything after the first number, which it detects as the volume! So it detects

“Black Hammer Vol3 Age of Doom.cbz”

as

“Black Hammer” #3

This is annoying! Because now it’s not finding the collected volume 3 ‘Age of Doom’, it’s pulling down data for the third single issue.

So one way would be to name it like

“Black Hammer Age of Doom.cbz”

“Black Hammer The Event.cbz”

But now, in Windows (or your operating system of choice), you’ve lost all ability to sort your files alphabetically to get the reading order. ‘The Event’ should come first! So I settled on just naming it the first way,

‘Black Hammer Vol2 The Event.cbz’

‘Black Hammer Vol3 Age of Doom.cbz”

By naming in this way I can sort files by filename within the folder and keep it in reading order.

Unfortunately, it does mean a bit more work once we get it into ComicTagger, but being able to identify a comic by its filename and sort them alphabetically to get the correct reading order is very helpful. Especially if you end up having to run python scripts like I did.

5.3 Naming Standalone Books

For other comics like specials, one-offs, etc, I just use the name of it.Ideally with the year in brackets, but it doesn’t really matter because there’s no reading order for standalone books!

“47 Ronin.cbz”

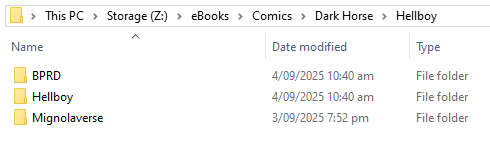

Part 6: Folder Structure

The folder structure does come into play for Kavita, as far as I know books that should be grouped together must be under a shared folder.

For an IP that has a lot of spinoffs or series, I separate the files into separate sub folders based on how the comics would be separated into different ‘series’.

To help my own organisation, I went a step further and sorted my comics under publishers too. I didn’t bother with Manga because every manga I had was published by ‘Kodansha USA’.

Also, because of the way Comics and Manga are handled differently, it’s a good idea to split them up into their own folder structure.

I also ended up coming back and splitting off one-off comic books (graphic novels) into their own folder structure. It was nice having a separate library of books in Kavita that didn’t care about collections or series.

So, I end up with a folder structure like:

eBooks

- Comics

- - Dynamite

- - - Red Sonja

- - - - (2014) Red Sonja

- - - - (2016) Red Sonja

- - Image

- - - Paper Girls

- Manga

- - Drops of God

- Graphic Novels

- - Dark Horse

- - - 47 Ronin

Part 7: Metadata

Now you have your comic files, all converted to .cbz, with tidy file names that can be sorted in Windows and (mostly) interpreted by various software - let’s get some metadata!

7.1 ComicTagger

I use ComicTagger to interpret my comic files, search online for a best match, and then pull down comic data from an online fan-maintained comic database, comicvine.com. The most important data for me personally is that it pulls down release date information, which is really nice for knowing the order in which to read the books. It uses the filename and the cover of the comic to figure out what data to grab. It also grabs info like the book’s authors, plot summaries, etc. which work very nicely once it’s all set up on Kavita.

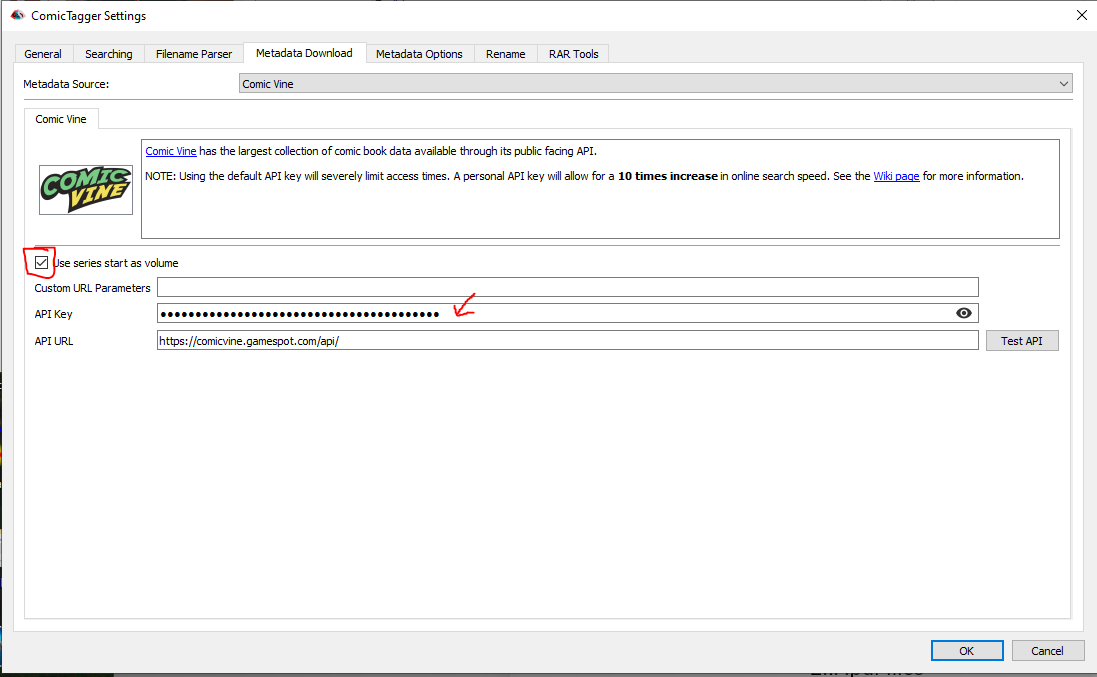

7.1b ComicVine API Key

One of the first things I suggest doing is creating a ComicVine account and getting an API key. It’s free and makes ComicTagger run a lot faster and crash a lot less. Once you have an account, grab your API key from here and plug it into ComicTagger in the Settings under the ‘Metadata Download’ tab.

Two ComicTagger settings I change - I tick ‘Use Series Start as Volume’ and I plug in an API key.

7.1c Use Series Start as Volume

This is a toggle I found too late. It’s in ‘Metadata Download’ section - see the above screenshot. It sets the ‘volume’ to be the year associated with the first issue of the ‘series’ the issue/volume belongs to. This is pretty handy for grouping comics under a single ‘run’ because Kavita combines the Series with the Volume to make a unique tag to group comics under. If all your comic files use Number as the Volume then you’ll end up with every file having a unique combination and nothing will group.

However, this only works when ComicVine agrees that the books are grouped. You may have to do some manual editing to group books by adjusting the Volume number in your metadata.

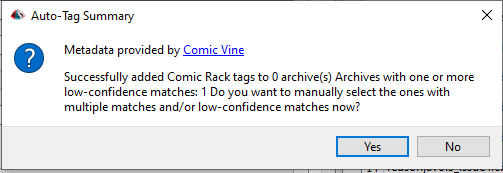

7.2 Pulling down Metadata

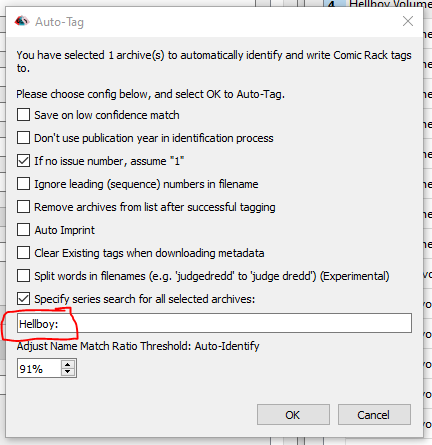

I use the ‘Open Folder’ which will display a list of files in the right-hand side of ComicTagger. Then I select all of the items in the list and click the ‘Auto-Tag’ option.

You can tag in bulk! It compares the image to make sure the volume is correct! Easy, right? Well.. no. You’re going to have to do a lot of babysitting.

If you have a lot of books, this is going to be a time consuming process. There are a few ‘Are you sure you want to save tags?’ popups that are quite annoying, but you can disable those. If you haven’t set up your ComicVine API key, definitely do that too.

7.2b No Matches

If you use the Autotagger and get no matches, there are a couple possible problems and ways to get around those problems.

The autotagger is extremely specific with filenames. If your book is labelled in ComicVine as ‘Hellboy: The Storm and The Fury’ and your filename is ‘Hellboy Volume 12 - The Storm and the Fury.cbz’, it will fail because it’s ignored everything past 12. If your file was named ‘Hellboy The Storm And The Fury.cbz’, it’d still probably fail due to the missing “:”! And filenames can’t have : in them!

One thing you can do for auto-tagging a group of comics when the name doesn’t match is to override the ‘series name’ for a group of comics in the Auto-Tag settings.

However, in the case of Hellboy, that won’t work, because, and this is a situation that is quite frustrating, each of the ‘volumes’ is a unique entry in ComicVine.

So you would have to do a search for ‘Hellboy: The Storm and the Fury’ individually to pull down information for that book, ‘Hellboy: The Wild Hunt’ for another book, etc etc etc… At this point you’re grabbing metadata one at a time. Frustrating and slow. I don’t know a good way around this.

I found that for volumes that had unique names, I had the most luck using the ‘Search Online’ option manually for each book.

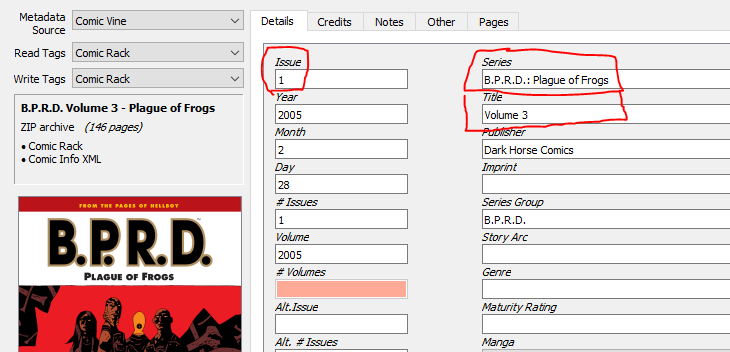

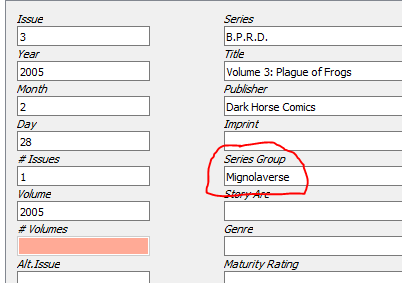

Then, you’ll be met with the next problem. This is how the metadata in ComicVine is set up for ‘B.P.R.D. Vol 3: Plague of Frogs’:

The issue is ‘1’, even though it is volume 3. The Series is the name of the book, ‘B.P.R.D.: Plague of Frogs’, but I’d expect it to just be ‘B.P.R.D.’. And finally, the ‘Title’ is ‘Volume 3’ where I’d expect it to be ‘Volume 3: Plague of Frogs’.

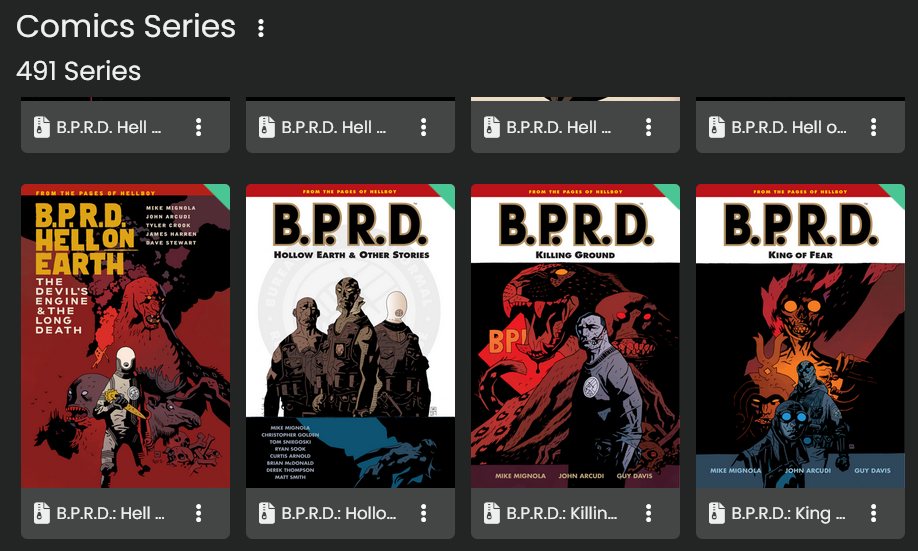

The result of keeping this data as it comes from ComicVine, is that you get this result in Kavita:

Every single volume is considered a unique ‘Series’!!

It is possible to use the ‘Series Group’ tag and the ‘Collections’ feature of Kavita to have a single space for the B.P.R.D. books, but ideally, I don’t want a ‘volume 3’ to ever be considered a ‘series’. So that’s going to take extra work for me to adjust that metadata.

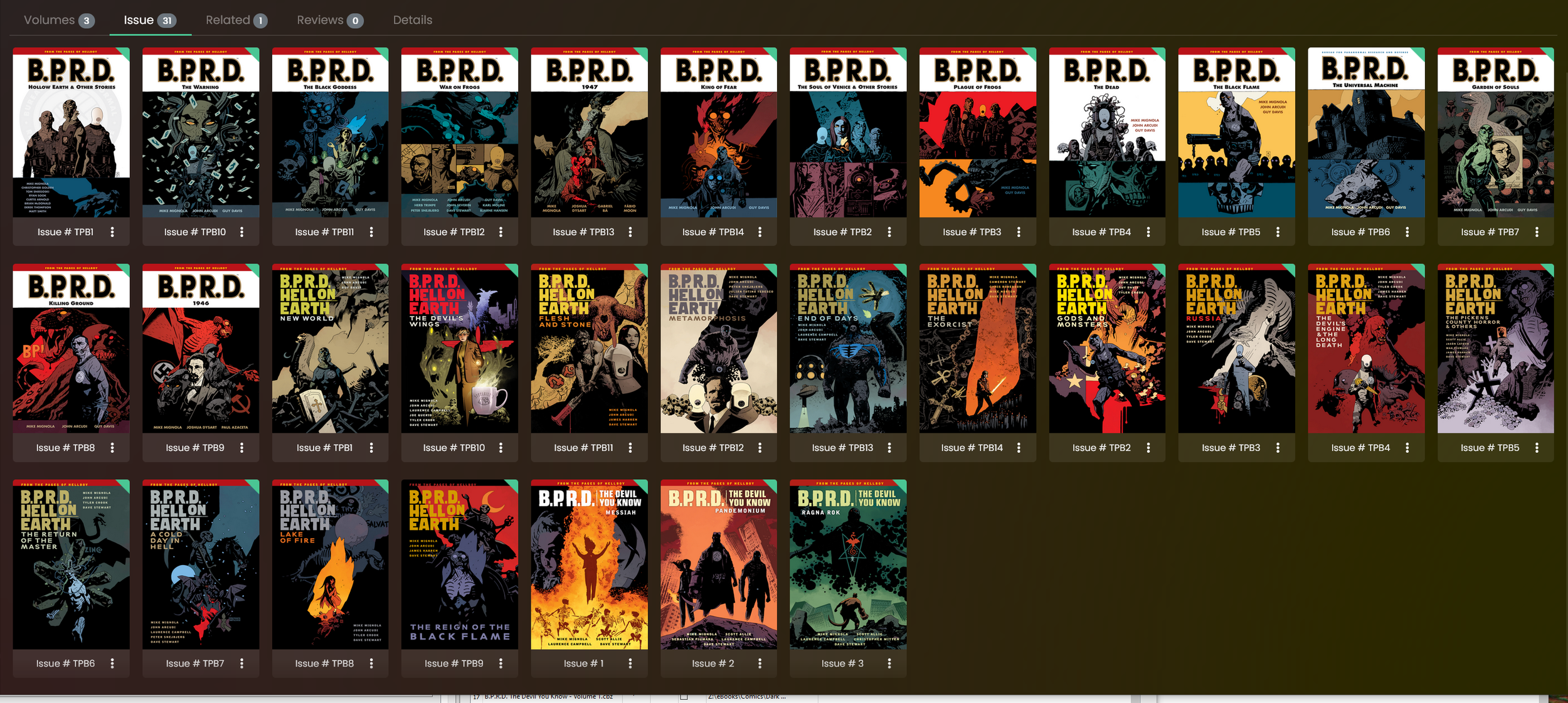

As an aside, I also saw some Kavita guide that suggested if you have ‘books’ instead of ‘issues’, that you can write TPB (Trade Paperback) in the Issue field, i.e. “TPB1”, “TPB2” etc. instead of just 1,2. This is meant to make it clearer that they are ‘books’ and not ‘issues’. However, this isn’t a good idea, because if you have more than 9 books, 10 gets sorted after 1. So you get them ordered like TPB1, TPB10, TPB11, TPB12, TPB2, TPB3, etc. I tried changing it to say TPB01, but ComicTagger doesn’t like the 0 in there. So I gave up on that idea.

I hope if you’re following along, you can get it much closer to what you want on your first pass. For me, I’ve been going back and forth tweaking filenames and metadata and settings for many days.

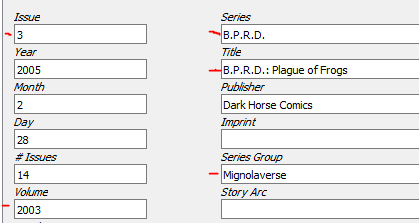

Here’s how I’m going to tag this series of volumes now. The red lines show the fields that I had to adjust myself.

I tag the Issue based on the book Volume so that it stays in order.

I set the Series as B.P.R.D., because that’s what I want all the books to come under.

I’ll change the ‘Title’ to the name of the volume.

I also need to change the ‘Volume’ number of every book in the series to match the ‘Volume’ of the first book! For example, B.P.R.D. Volume 1 has its ‘Volume’ set to ‘2011’ because that’s the release year. Volume 2 came out in 2012, so its ‘Volume’ is 2012. That means that book 2 is considered a different ‘Volume’ and makes it harder to connect book 1 to book 2.

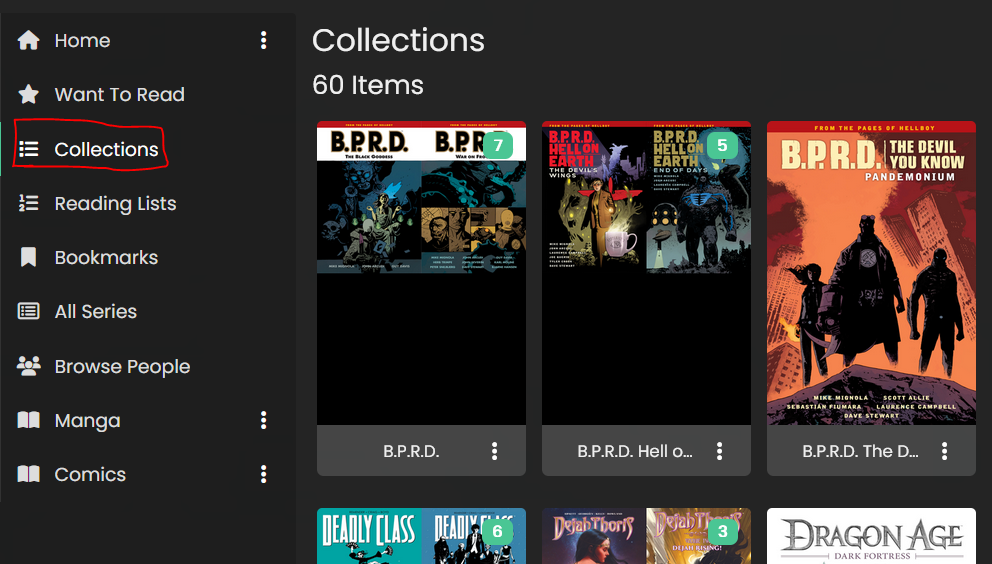

So, I go through all of my B.P.R.D. books and set their ‘Volume’ to ‘2011’. Now Kavita considers them all connected books. Huzzah.

Going a step further, I do actually use the way Kavita groups by ‘Volume’ (year) to my advantage. I renamed my books belonging to the ‘B.P.R.D. The Devil You Know’ series to the same series “B.P.R.D.'“, but I set the ‘Volume’ to the year of the first book in that ‘The Devil You Know’ sub-series.

I also set the ‘Series Group’ to Mignolaverse, because that generates a ‘Collection’ called Mignolaverse that also includes my Hellboy books. This is a great field for grouping different series that belong to the same ‘world’!

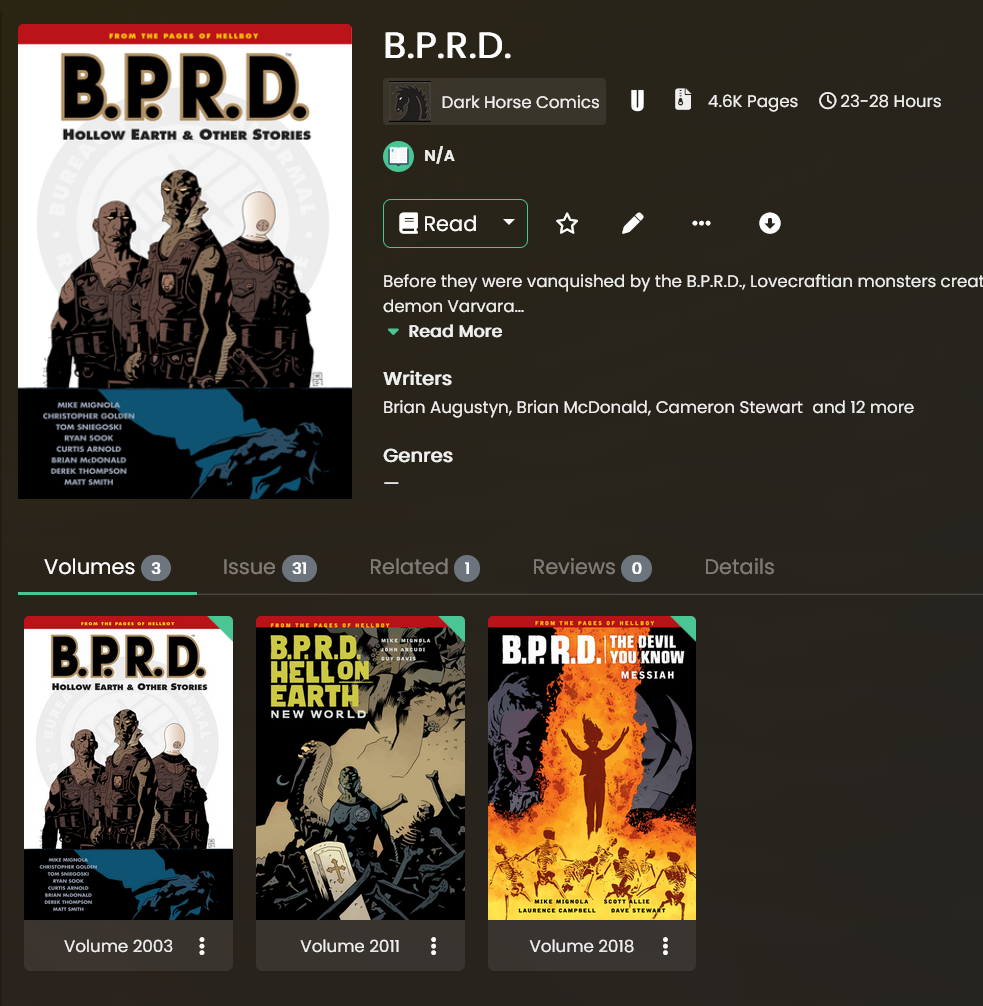

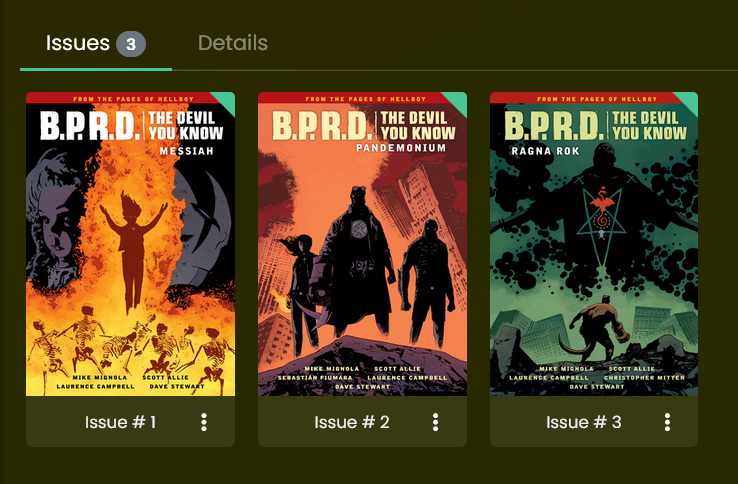

Here’s the result. Now B.P.R.D. is a single ‘Series’:

And when I click on it, I see the main ‘B.P.R.D.’ books as well as the sub-series ‘Hell on Earth’ and ‘The Devil You Know’ as separate ‘Volumes’ of the same series:

If I click on one of those Volumes, I see the Books within it as ‘Issues’:

And I also get to see all of the books from all of the sub-series under the main B.P.R.D. series too, by using the ‘Issue’ tab!

It took me a lot of trial and error to get here and find the settings to organise my books the way I want to find them. It’s still not quite perfect, like I’d like it to say ‘Books’ rather than ‘Issues’, and maybe either show the year of each item or be able to sort each book file by release date. Still though, this is definitely good enough!

7.2c Multiple Matches

If you use the Autotagger and get a popup saying there are multiple matches, you will get a second popup where it gives you some partial matches and you are able to select the one that best matches your book file.

However, this doesn’t work correctly! It won’t actually save to the file. So if this happens, you have two options:

Manual Search:

Select the issue that it couldn’t auto-tag, then use ‘Search Online’. This is slow and annoying.

Removing unwanted publishers:

This is a process that I found helped a lot with speeding the whole process up, by blacklisting certain publishers from being picked up by the Autotagger, it’s far more likely to grab the right series and issues, and lets me work in bulk again.

Above, ComicTagger has struggled to pick up on which exact ComicVine data to use for my book, as the name matches a few possible books. Tricky! However, there’s a way to get it to more accurately pick the right one: take a note of the other Publishers, and add them to the Publisher Blacklist. In my case, my books are published by ‘Kodansha Comics USA’ - the other entries listed are generally for different translations of the same book.

So, I add the other Publishers to the blacklist in this option:

Make sure ‘Enable the publisher filter’ is ticked as well.

Now, when you run the Autotagger, it will ignore results from the publishers you’ve listed, and hopefully just get it right first time and let you bulk tag again.

7.3 Series Group

One optional tag that I think is worth setting for your books is ‘Series Group’. This is especially handy for comic ‘universes’ that encompass multiple series. For example, the ‘Mignolaverse’ encompasses Hellboy, a few different B.P.R.D. series, and some various standalone books.

If I tag all of the books under these series with the ‘Series Group’ of ‘Mignolaverse’, then I can have Kavita generate a ‘Collection’ that contains all of the books under this umbrella.

It’s probably not worth setting on regular series, this is more useful for a series that contains other series!

In my initial tagging, I was a bit heavy handed with the ‘SeriesGroup’ tag so I had to do multiple passes to strip some of those tags out. In the end I settled for the idea that only multiple different Series that had some connecting tissue (i.e. Hellboy and B.P.R.D.) should have a Series Group. Any group of books that came under the umbrella of just one series didn’t need to be part of a collection.

7.4 Crashes

ComicTagger crashes all the time for me. I just keep an eye on it and if the progress bar hasn’t moved for a while, I just close it all down and open it up again.

Sometimes it crashes due to exceeding the rate limit for ComicVine. Getting an API key cuts down on this type of crash, but doesn’t eliminate it entirely. Sometimes if it keeps crashing, you just need to go away and come back an hour later.

Annoying but it hasn’t caused any issues so far.

7.5 Calibre

One ebook metadata system that will come up a lot if you’re looking for ways to tag your book files with metadata is Calibre. It’s a great application for managing traditional text books, but it has a pretty big flaw - it manages your books by creating a duplicate folder structure of your ebooks. This kinda sucks for comics, because comic files are huge!

Plus, as far as I can tell, it requires you to tag everything manually (albeit in bulk).

So, for that reason, I stuck with .cbz and ComicTagger.

Part 8: Kavita

Now you have hopefully gone through and tagged everything.

Kavita is an open source book hosting service.

I won’t go into all the details of setting a home server up, or Kavita - I just followed the instructions for Linux on their own installation guide and set it up on a second-hand mini PC I leave on and connected to my router via ethernet.

I found the Kavita setup process fairly straight-forward, so I would say just follow their guides!

8.1 - Set your hosting device’s IP to be locally static

One step that I think is necessary is to adjust your router settings so that your mini PC’s mac address has its own reserved local IP address. This is really important otherwise every time your router resets or your mini PC resets, it could change its IP address, and force you to figure it out and re-connect it. Sometimes it’s called ‘IP Reservation’ under ‘DHCP Settings’ in your Router’s settings. Hopefully your router supports this!

8.2 Kavita Library Settings

One thing to note is that Kavita has separate Library types for ‘Book’, ‘Comic’, ‘Manga’, and ‘ComicLegacy’. The difference between Comic and ComicLegacy is pretty nebulous. It sounds like if your collection is mostly individual issues, rather than collections and volumes, ‘Comic’ library type along with ComicVine metadata is the best option. Otherwise, perhaps Comic (Legacy) is better. Honestly, it sounds like both are going to be a pain in the ass one way or another, especially if your collection has no rhyme or reason like mine, just various comics from bundles!

I set up three Libraries:

Comics (ComicLegacy type)

Manga (Manga type)

Graphic Novels (ComicLegacy type).

8.3 Ready to Test

Once you’ve got all your files downloaded, named, sorted, metadata’d and copied to your server’s Kavita folder - you’re ready to check it out and see what went wrong!

In my case, when I got to this point, I realised that:

8.2b: My epub files had incorrect metadata

My epubs had different metadata, because the ComicTagger metadata I’d put into them was only compatible with .cbz files and was being totally ignored. The metadata in these books was whatever the Publisher had put in them, and it had concatenated the volume number into the series name, so all my .epub files were all considered different series. Ow!

After trying to figure out a better solution, I just decided to convert all my .epubs to .cbz.

This was when I ran into another problem - because I had run ComicTagger on all my .epubs, it had put .cbz metadata into all of my .epubs, and this prevented the epub2cbz application from processing my files! Ow! Ow!

So, I had to make a python script that stripped out the ComicInfo.XML metadata file from all of my .epub files. Then I could run them through epub2cbz, and then I could run them through ComicTagger again.

8.2c: My cbz books weren’t grouped either!

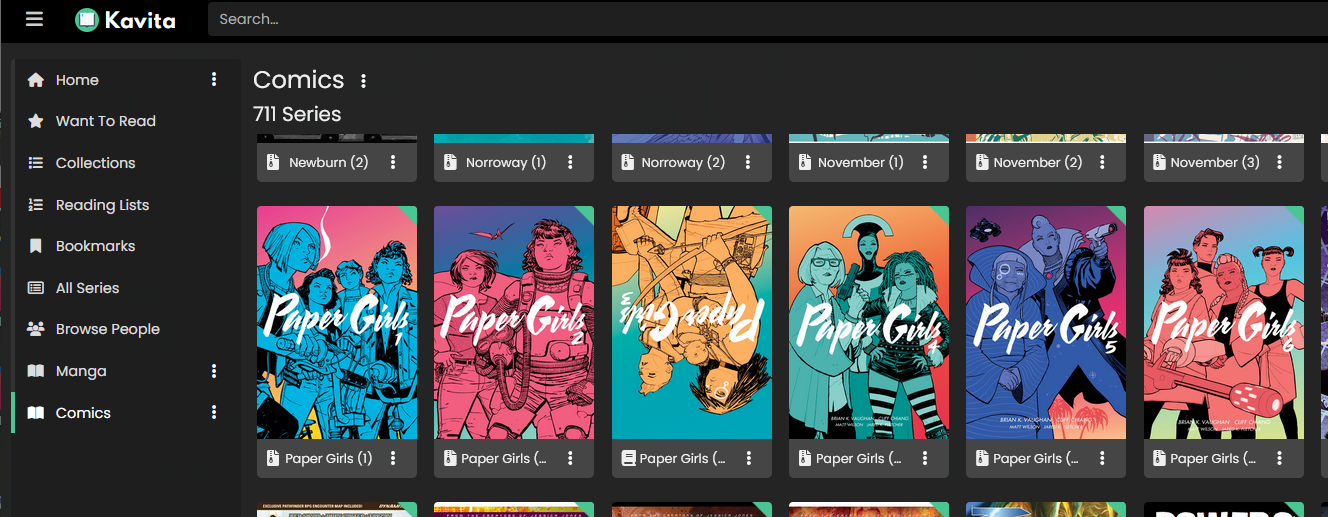

Kavita creates a ‘group’ by pairing the ‘Series’ with the ‘Volume’ (assumed to be a year). However, my files were all tagged by ComicTagger so that Volume was the same as the ‘Number’ tag. This meant that just about every book I had uploaded was considered a different series. This makes it almost impossible to navigate. Gah!!

This was fixed by using the ComicTagger setting ‘Use series start as volume’ and… re-tagging all my files. Agh!

If you’ve been following the guide up until now, hopefully you’ve avoided this problem.

‘Paper Girls’ should be a single series, not considered six different series…

Part 9: Tweaking

So, I had to go back to the drawing board a bit. I’ve tried to lay this blog/guide out in a way that you won’t run into the same issues I had. I was in the middle of correcting all of the mistakes I’d made when I decided to write all this down for posterity.

I decided I wanted to think a bit more about how I wanted my books to show up in Kavita - what books should be grouped and what shouldn’t. Learning how Kavita decides what to group and what to count as a separate series was not obvious to me. I really wish I could just keep my folder structure within Kavita as how I keep the files in Windows.

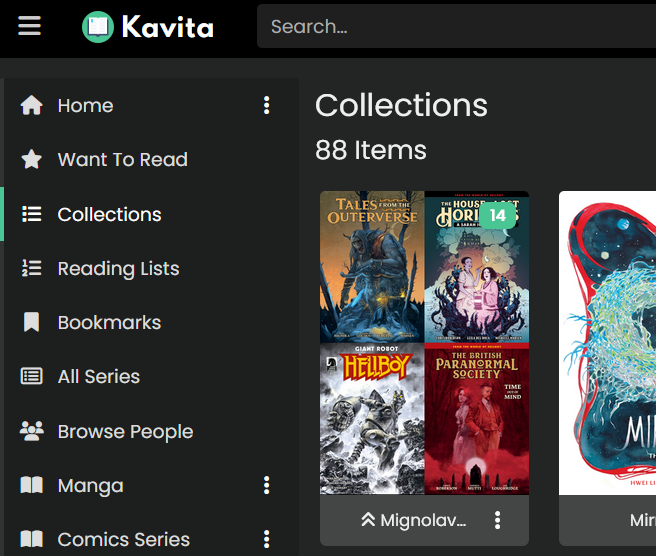

9.1 Collections

One thing I wanted to do was to have a way to gather similar comics together. For example, Mike Mignola’s Hellboy series encompasses the main ‘Hellboy’ series, Hellboy spinoffs, the ‘B.P.R.D.’ series and its spinoffs, and a bunch of other standalone titles that take place in the same universe. I wanted somewhere to gather the books.

Kavita’s Collections feature seemed good for this!

It uses the ‘SeriesGroup’ metadata tag to group books in a separate place to the ‘Series’ category.

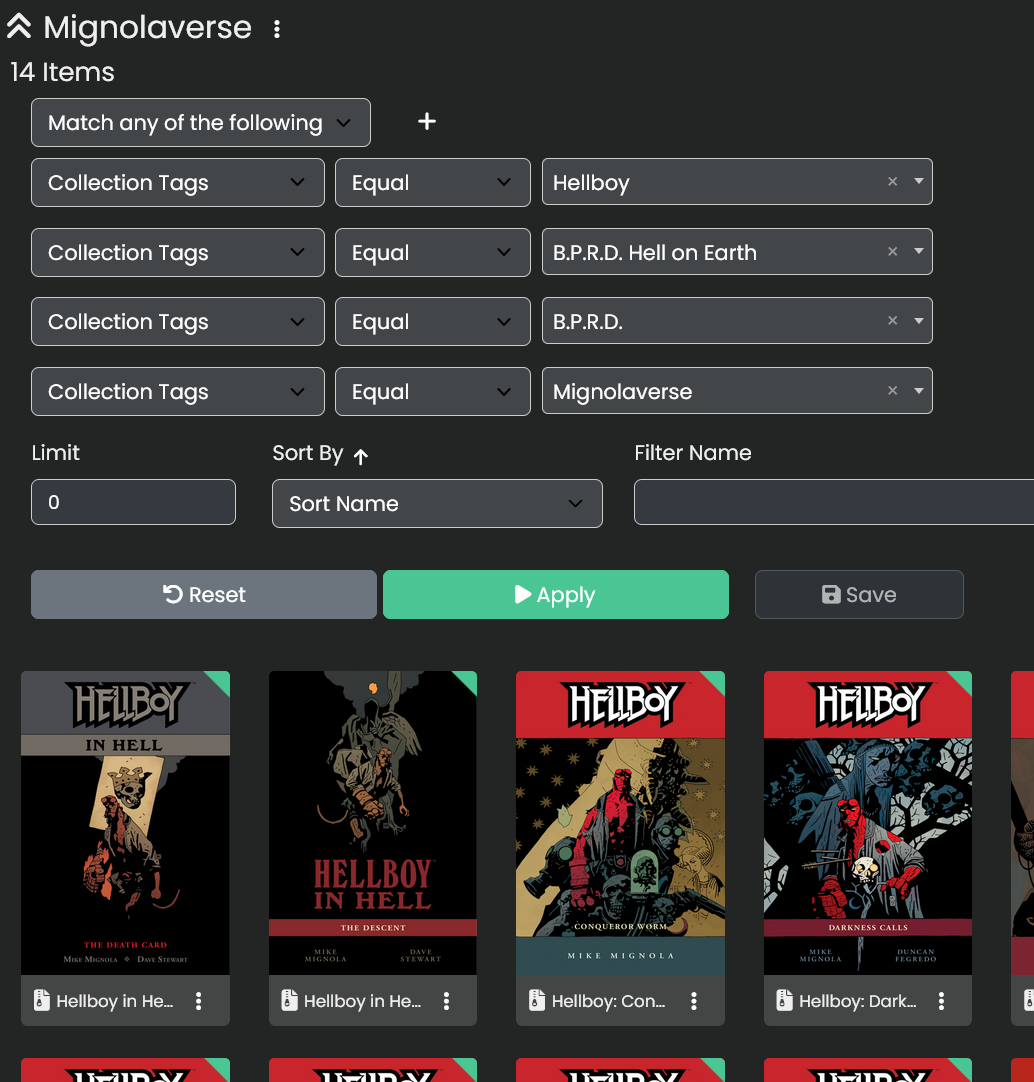

Initially my books that had different ‘SeriesGroup’ tags, but I wanted to try and set up a collection to encompass all of the ‘Mignolaverse’ books. I found this ‘Filter’ feature on the Collections,

HOWEVER! It doesn’t seem to work. Even with the ‘match any of the following’ condition, it gives up after the first one, and it doesn’t actually save. So the feature is no good to me! I needed to go back and set up my ‘SeriesGroup’ metadata tag.